AI policy for the application layer

aka: What the UK’s Action Plan should say

AI policy is often very macro:

How much compute do we need? (More!) How much capital do we need? (More!) How much spinout equity should unis take? (Less!)

This stuff absolutely matters, but often it’s way too disconnected from the operating reality of today’s AI founders.1

Similarly, although it’s right for the UK to think about the foundation layer of AI policy and how to navigate the hypertrainers, that market is (mostly) won and most of the opportunities available to the UK will be in the application layer.

So if you’re a UK policymaker who cares about startups, you should focus on a) easing founders’ operating reality, to b) unlock new opportunities at the application layer. For AI startups, that means clearing the barriers to accelerating specific verticals, like medical devices, drones or autonomous vehicles.

That requires doing things differently:

New, AI-first startups aren’t well supported by existing regulatory and procurement pathways, and

Opportunities at the application layer require their own, distinct interventions

Although it’s tempting to ask what DSIT can conjure up alone, cross-cutting principles can quickly become lowest-common-denominator policy. In reality, we need every department and regulator to be driving AI diffusion across their own patch, tackling regulatory and procurement blockers where founders can do everything right on paper, yet still be held up by forces outside their control. And that requires deep political and intellectual sponsorship not just in DSIT, but in No10: not to centralise control, but to empower, cajole & enforce pro-AI policy across government.

This was our focus last week, when we went to 10 Downing Street last week for a roundtable as part of the new government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan. What follows is part-readout, part recommendation.

Why AI is different

A lot of policy folk’s starting point for accelerating AI’s benefits is to ask how and where to ‘apply’ it. But ‘applying AI’ implies you’re keeping the existing workflow, like putting a newspaper PDF on the web and calling it ‘digital’.

Instead, new paradigms expand capabilities and require a re-think of user needs: we’re in the process of a whole load of technical, product and design evolution to configure natively AI-first services. To enable these new approaches to scale, procurement & regulator processes are going to need to change too. Let’s take those one by one:

Scaling AI-native services demands new approaches to procurement

In a recent interview, DSIT Secretary of State Peter Kyle offered one of the best explanations I’ve heard from a politician for why technology matters so much:

I went to a hospital where their radiography department is fully integrated with AI. When people go in for a scan…it’s very effective. It takes seven seconds. If my mum had been scanned with this, she’d be alive today.

…

When you start thinking of AI in those terms…this isn’t distant 0s and 1s flicking across a screen. These are deep driving forces and emotions, the very essence of what it means to be human.

It would be great if every bit of the NHS had this sort of absorptive capacity for AI. Yet all too often, tech procurement in the NHS is fragmented, slow, duplicative, bespoke and sub-scale. Nor is the answer to centralise everything, everywhere: standardised, national commissioning frequently fails due to limited Trust take-up, given varied needs and priorities across the country.

But regardless of why they exist, these barriers have led many VCs simply to see NHS healthtech as uninvestable. The Action Plan should set out to fix both the reality and perception here, to encourage a viable & successful pipeline of AI innovation in the NHS and to convert that into tangible impact for patients.

We won’t pretend we can solve ‘all NHS procurement’ here, although we have been thinking about how to align patient, regulatory and commercial incentives to scale NHS AI specifically. Nor is ‘AI in the NHS’ a single category: Trusts will always go at different speeds depending on their local needs, whether it’s empowering radiographers with an AI medical device or using AI to triage appointments by need.

But there is one win-win that we should absolutely prioritise: self-referral for at-home, AI healthcare.

Instead of stuffing ever more care into an expensive, in-person, GP- or hospital-centric model that makes patients wait weeks on end purely for an initial consultation, AI allows us to do thing differently. We can make personalised, high quality care available on day 1, cheaply and easily, tackling spiralling backlogs in the process.

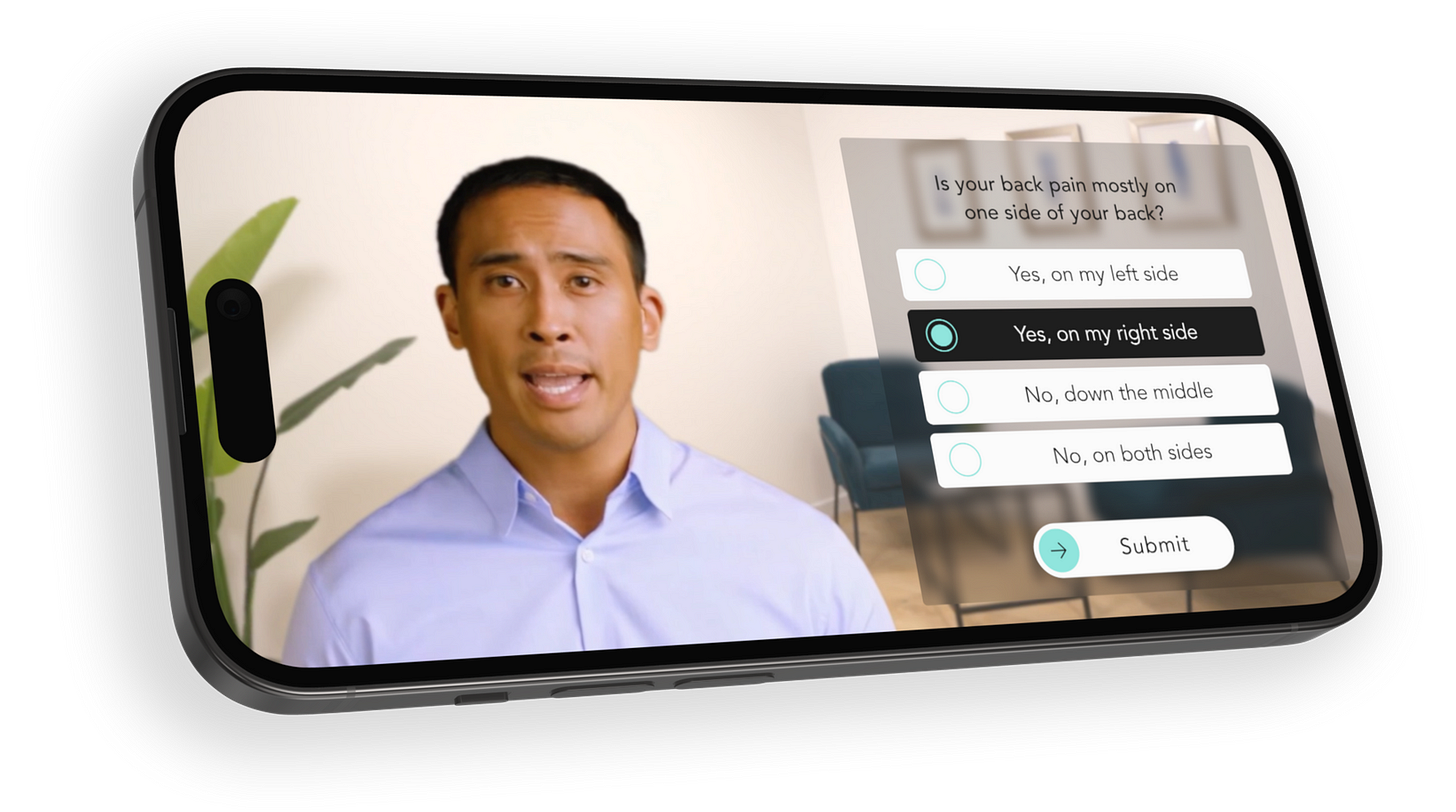

We see a version of this with Flok Health, the UK’s first autonomous physiotherapy clinic, providing personalised MSK treatment at population scale. With MSK issues growing, we will never have enough physios to meet demand. But Flok can provide same-day appointments digitally, instead of patients needing to wait 13+ weeks to see someone in person. And because they’re available 24/7, they can work around people’s work and family lives unlike a normal appointment: so it’s no surprise their most popular time is 8pm on a weekday.

Yes, Flok is an AI company. But the most interesting thing about them is how AI allows them to deliver what was once impossible: treating people immediately, before issues get worse, and diverting them away from a legacy, expensive, rigid model of care. Today, fragmented procurement means care like this is only available in a handful of places across the country. But why shouldn’t someone living elsewhere be able to access it too? The NHS app could be a platform for a whole plethora of self-serve services sitting on top, but we need novel commissioning and reimbursement pathways to allow it. The old constraints of the physical world no longer apply. We should act like it.

[There are lessons here too for procuring AI in defence and other public services, but for now we’ll point to work by others like Airstreet and PUBLIC for recommendations there.]

Fix the regulators to help AI companies move quickly

As Kate Jones (DRCF CEO) said in our recent interview, "AI is not a sector, it's going to permeate everywhere”. In that vein, after the last government’s AI white paper, 13 different regulators set out their ‘strategic approaches to AI’:

But in practice, this exercise essentially asked the 13 organisations to set out how 5 ‘AI principles’ would apply in their sector:

safety, security and robustness

transparency and explainability

fairness

accountability and governance

contestability and redress

No one can argue with these principles, but that’s the point. The benefit of not having an economy-wide AI Act is that AI regulation should flex according to its context, rather than defaulting to generic, lowest-common-denominator principles.

This is also why the list above doesn’t include the regulators for autonomous vehicles (Vehicle Certification Agency), drones (Civil Aviation Authority), or many other sectors. On paper, these organisations don’t look like ‘AI regulators’. But nearly every regulator is now an AI regulator:

AVs: how many people have heard of the Vehicle Certification Agency? It’s tiny, but generally regarded as a highly capable regulator (notably, with a mixed industry-government funding model and incentive structure). Intriguingly, it’s learning from work by the MHRA and others to develop a model for assuring continuously iterative AI systems in safety critical environments, which are a poor fit for traditional regulatory processes. Contrast a static x-ray machine with a continuously evolving AI medical device: we have frameworks for authorising stable, discrete products, but it’s not practical to require iterative AI systems to be re-certified every time there’s a significant change. How many other regulators in safety-critical settings will need to adopt and tailor a similar approach to their sector? Just as the ‘Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum’ (DRCF) was established to upgrade capability across ‘digital regulators’, we’re going to need an equivalent forum for nearly every regulator to build capacity, particularly given limited supply of technical hires.

Drones: there are huge opportunities to transform medical supply chains, logistics and many other applications via drones, but here the CAA is dragging its feet on allowing drones to fly beyond a threshold known as ‘visual line of sight’ (BVLOS). Critically, this is not because of a legislative barrier, it’s just because the regulator gets all the blame if something goes wrong and has zero incentive to accelerate any benefits. The issue isn’t that the CAA weren’t on the list above — asking them to respond to 5 generic principles isn’t productive — it’s that we needed a distinctive approach from the start, to cajole a risk averse regulator into supporting innovation.

Across many regulators, AI guidance is also still mostly written on the assumption it will be read by legal and compliance staff, not product managers and content marketers who are new to regulated markets. Similarly, advice services should be proactive, not reactive, reducing the burden on founders and using data the government already has — from companies house, HMRC, Innovate UK, and startups’ websites — to offer personalised support. The pilots that exist today are well-intentioned and respond to a genuine need, but have a lot of headroom to improve.

Fixing the UK’s regulators is a critical part of AI policy for the application layer. We need to radically upgrade regulators’ resource, rules and risk appetite towards AI. This is how you deliver tailored approaches, for heterogenous applications, in different verticals.

The government’s commitment to establishing a Regulatory Innovation Office is promising here, but it needs to be backed up with budget, powers and political sponsorship if it’s going to incentivise or enforce behaviour change on other departments and regulators. It should:

Have a £100m budget agreed upfront with HMT, akin to AISI, to invest in regulatory innovation projects [replacing the old Regulatory Pioneers Fund]

Drive regulatory innovation across government by:

Surfacing, triaging and prioritising legislative change requests from regulators.

Lobbying HMT & departments for annual regulatory budget increases, to recoup recoup core, ‘business-as-usual’ capacity that has eroded in recent years

Keeping a public register of strategic steers requested by regulators

Requiring departments to explain why pro-innovation changes have not been taken forward

Monitoring regulatory performance, with the NAO and ONS, to explicitly encourage regulatory innovation by tracking approval backlogs and regulatory budgets over time, building comparable performance indicators, and estimating the cost of delayed and foregone innovation

Exploring how this unit could become a radically new, cross-sectoral innovation regulator, as a long-term solution for frontier, disruptive innovations test the limits of legacy, sectoral regulator structures

Coordinate strategic steers from Departments to their sponsored regulators, committing to the view that short-term conservatism ultimately leaves consumers worse off in the long run

Scope out new pathways for the UK to have the fastest regulatory approval timelines globally, including ‘pay for speed’ options and expanding international recognition procedures

Establish and chair an AI Regulatory Innovation Forum, expanding beyond the DRCF to incorporate other regulators at the frontier of AI, such as the MHRA, CAA and VCA

Check out our Fix The Regulators campaign for more detail:

Fix The Regulators

Creaking regulatory capacity is constraining economic and startup growth. Let's fix it.

Most AI policy discussions are almost completely disconnected from the startup founder point of view and the reality of their day-to-day decision making. There is way too much high-level waffle, and way too little attention on what AI policy will really mean or how to navigate it.

Take the EU AI Act: for many AI founders, the practical implication is to divert scarce resource away from productive activity (e.g. moving quickly to build and sell your product) into unproductive, time-and-energy-sucking activity (e.g. re-allocating budget towards compliance headcount instead of engineering talent, spending time doing risk assessments instead of speaking to new customers, etc.).

The point of this illustration isn’t to critique the AI Act. You might believe it’s a reasonable attempt to mitigate risks, although even the architect of the Act is now having doubts.

Instead, the point is to ground us in the operational reality of a startup founder. Like it or not, early-stage AI founders are now speedrunning what it takes to build a company in a regulated market. They might have an eye on any or all of these issues:

Product:

Debates about, and their company’s reliance on/exposure to, open source models

Copyright and legal liabilities (whether they’re training their own models or deploying on top of others’)

Accessing training data

Go-to-market:

Sectoral regulators developing their own bespoke rules, in areas like fintech, health, drones or autonomous vehicles.

Slow procurement processes where government is a buyer, in health, defence and other public services

Enterprise customers hesitating to sign contracts due to regulatory risks

Finance & Ops:

The cost of compute, and its relationship to obstructive planning rules, a broken R&D tax credit system, competition investigations into cloud providers, and several other policy-adjacent domains

The cost and ease of hiring exceptional AI talent both within the UK (where noncompetes are growing) and from outside it (with visa costs & processing times both spiralling)

The lack of insurance products and other forms of liability protection for AI systems

This is an inexhaustive list (& we’d love to hear other examples!)